Commerce and Kinship

商务与亲属关系

Pepper and Gambier

甘密胡椒农业

Beginnings (1820s-30s)

农业初期(1820-30年代)

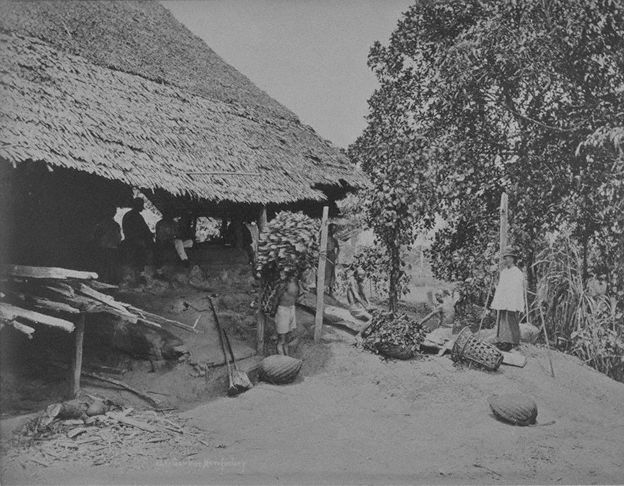

During the late 1820s and early 1830s, Eu Chin tried planting tea, nutmegs, and other crops, but was unsuccessful. 23 Buckley, Anecdotal History, vol. 1, 151. Nutmeg planting was more popular with European planters than with the non-Europeans. 24 H.N. Ridley, “History and Development of Agriculture in the Malay Peninsula,” Agricultural Bulletin of the Straits and Federated Malay States 4 (1904): 299. Until the introduction of rubber from Brazil by H.N. Ridley, however, Europeans were not as successful in their attempts at plantation agriculture in Singapore than non-Europeans. The Europeans were misled into thinking that “the soil is generally good … on seeing the gigantic trees and thick underwood of which the interminable forests are composed,” 25 J. Balestier, “View of the State of Agriculture in the British Possessions in the Straits of Malacca,” Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia, 2 (1848): 141. little knowing that in the tropical forest, topsoil is thin and washes away quickly after the original vegetation is cleared, leaving a barren layer unsuited for cultivation. It is possible that Eu Chin first took up planting these crops because he was being advised by Europeans, as he was given encouragement by Thomas Church to persevere when his initial attempts were unsuccessful. 26 Buckley, Anecdotal History, vol. 1, 151.

What is Gambier?

甘密是什么?

Gambier is a plant, known botanically as Uncaria gambir, that is related to the coffee bush (belonging to the same family, Rubiaceae). An extract of gambier leaves was used as a tanning agent for tanning leather and dyeing fabrics. The process of tanning is used to prepare raw animal hides. Substances called tannins in the leaves of gambier and other plants are responsible for their astringent taste, for example in the bitterness of tea. Tannins bind to proteins in the animal skins and denature them, making them tough and resistant to decay. Gambier had been grown on a small scale in Southeast Asia long before Seah Eu Chin. He was fortunate that he went into gambier planting just as the demand for gambier extract was being driven up by industrialized leather production during the Industrial Revolution in Britain.

甘密(学名Uncaria gambir)是茜草科的一种植物。甘密叶含鞣质,提取之后用来制革和印染。茶叶也含鞣质,使茶的味道苦。鞣质使皮革里的蛋白质性质改变,让它更多坚固而不容易分解。十九世纪初,东南亚已经有小规模的甘密种植。幸运的,佘有进开始种甘密的时候,英国的工业革命使鞣质的需求和价值增长。

Eu Chin eventually succeeded by switching over to the planting of pepper and gambier, which were the dominant crops of the Asian planters. By 1832-4 he was doing well enough to occupy houses at the end of Elgin Bridge that were probably built by Kim Swee, and subsequently to buy them. 27 Buckley, Anecdotal History, vol. 1, 151, quoting Guthrie. In 1835 he acquired the rights from the East India Company to cultivate gambier and pepper over a large stretch of land “extending countrywards for 8 to 10 miles from the upper end of River Valley Road along more or less what is now Irwell Bank Road to Bukit Timah and Thomson Roads.” 28 Lin, “Local Chinese Worthies,” 81-82. Thus began the venture that would make him his fortune and reputation.

According to Lim Boon Keng’s biography of Eu Chin, “tradition has it” that Eu Chin introduced pepper and gambier to Singapore from Lingga near Rhio (Riau) and from Acheen, 29 Lin, “Local Chinese Worthies,” 82. but this “tradition” is certainly mistaken. Although he was one of the most prominent investors in pepper and gambier agriculture, he was a comparative latecomer to the enterprise. The Riau islands lie to the south of Singapore, and Chinese cultivation of gambier in Riau already had a long history linked to the relative independence of the Chinese settlements there. They were established in the 18th century, from about 1740-84; subsequent independence (1784-1819) was driven by conflict within the indigenous Malay population of the islands, leaving the agriculture almost solely in the hands of the Chinese settlers. 30 Carl A. Trocki, Prince of Pirates: the Temenggongs and the Development of Johor and Singapore, 1784-1885 (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 1979), 132-139. Contrary to common belief, 31 Paul Wheatley, “Land Use in the Vicinity of Singapore in the 1830s,” Journal of Tropical Geography 2 (1954): 63-66. However, he cites Carl Gibson-Hill as saying that there was evidence for gambier-planting before the British arrival gambier planting took root in Singapore even before Raffles’s arrival, in the form of small Chinese-owned gambier plantations on Mt. Stamford. 32 Notice by J.P. Bernard (10 May 1822), Straits Settlements Records [SSR] L6, National Archives of Singapore. These planters probably came from Riau, and the historian Yen Ching-Hwang 33 Yen Ching-Hwang, A Social History of the Chinese in Singapore and Malaysia 1800-1911 (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1986), 121. asserts that they were the founders of the Teochew community that was responsible for constructing the Watt Hai Cheng Temple. J.C. Jackson speculates that they might have come as early as the 1790s to flee the turmoil in Riau. 34 J.C. Jackson, Planters and Speculators: Chinese and European Agricultural Enterprise in Malaya, 1786-1921, (Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya Press, 1956), 7. Gambier had also been cultivated on a small scale in the Malay Peninsula since the 18th century. 35 Ridley, “Agriculture in the Malay Peninsula,” 305. Hence, gambier cultivation in Singapore was initially a natural outgrowth of the kongsi-organized cultivation in Riau.

Previous (Pepper and Gambier) | Back to Life| Next (Maturity)