Commerce and Kinship

商务与亲属关系

Revenue Farming and Later Years

包税制与晚年

Relationship to the Opium Revenue Farm

与鸦片包税权的关系

In 1864, Eu Chin retired from business at the age of 60, leaving his two eldest sons and Tan Seng Poh in charge of his business. 92 Lin, “Local Chinese Worthies,” 84. Liang Seah, the second son, had married at the age of seventeen and soon afterwards became a secretary in the firm. 93 Lin, “Local Chinese Worthies,” 82-83. Although Liang Seah would later become the most successful and most prominent of Eu Chin’s sons, for the moment the business was in the hands of his uncle Tan Seng Poh and his older brother Cheo Seah, who was listed in 1872 as the manager of Eu Chin Co. 94 Singapore and Straits Directory (1872). Despite the handover, Eu Chin retained much influence behind the scenes; his company was still associated with his name years after his retirement. In 1873 the Singapore and Straits Directory ran for the first (and only) time a section titled “Principal Chinese Traders Dealing with Europeans”, and still listed his company, chop Chin Hin of North Bridge Road, under “Sea Eu Chin.” 95 Singapore and Straits Directory (1873), 18-19, section B, under ‘Teotchew’. This also tells us that Eu Chin, unlike the majority of Chinese traders, had access to European capital and links to the European market. By this time his brother-in-law Tan Seng Poh had his own listing in the directory, and was well known to Europeans and the colony at large as one of the proprietors of the Opium Farm, the excise farm responsible for the bulk of Singapore’s revenue. 96 Trocki, Opium and Empire, 72. Figs. 2 and 3 show that the greater fraction of Singapore’s revenue came from opium.

佘有进1864年于60岁退休,而商行的继任者是长子石城、次子连城、和内弟陈成宝。佘连城17岁已结了婚,之后在公司当书记。虽然连城晚年时在他兄弟当中是最有成就的,公司在当时是由他的伯兄(根据《商行名录》在1872年是“有进公司”的经理)和舅舅控制的。佘有进在背景还有很大的权势。1873年的《新加坡海峡商行名录》所登记的“主要的与欧人交易的华商”包括佘有进与他的振兴公司。

What was the Opium Farm?

鸦片包税权是什么?

The economics of pepper and gambier farming in 19th-century Singapore cannot be understood separately from opium farming. The cultivation of pepper and gambier only offered relatively slim returns that fluctuated depending on the market price offered for them. The true profits were to be made by whoever held the opium monopoly.

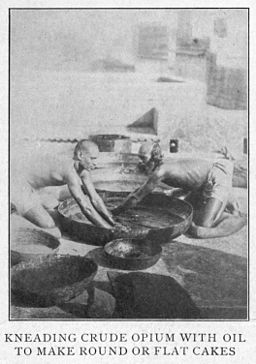

The term “farm” can be misleading. Opium was not cultivated in Singapore but came mostly from India; what was “farmed” was not the crop but instead the tax on opium. The colonial government offered a contract, to the highest bidder, that gave the monopoly on dealing in opium in return for the amount paid on the bid, which was essentially an indirect tax on the good paid upfront, which the “farmer” recouped when he sold the opium. Because Singapore was a free port, it had to raise most of its money through these tax farms, which included opium, spirits, and gambling.

It made sense for the gambier and pepper cultivators to be paired with the opium farmers. Whoever controlled cultivation also controlled the labourers, who were simultaneously a captive market and the main consumers of the drug. Whoever controlled opium had access to capital that could be ploughed back into the plantations for supplementary profit. Hence one could become very rich by controlling the distribution of opium to the franchise shops run by the kangchus. However, an opium farmer could easily be undercut by smuggling of opium by his rivals, because he would gain no profit from transactions not under his control. At the time that Eu Chin ostensibly retired from active business, Seng Poh was maneuvering to gain control of the opium farming monopolies of Singapore and Johore.

The complex plots and counter-plots in the 1860s between Seng Poh and his chief rival, the Hokkien Cheang Hong Lim 章芳琳 (son of Cheang Sam Teo 章三潮 , who had held the spirit and opium farms in Singapore, and possibly also Johore) are best recounted by Trocki in his book Opium and Empire. 97 Trocki, Opium and Empire, and “Tan Seng Poh”. Here I shall focus on how Seng Poh’s success was based in great part upon the resources available to him from his brother-in-law’s pepper and gambier interests. Firstly, the capital available to him allowed him to run the expense of undercutting his competitor, and of making bids for the farms. Revenue farms had an intensifying effect on wealth – only the wealthy could afford to bid on them, and winning the bid usually made one even wealthier. But if one won the bid by proposing too high a price, or if one was being undercut by smuggling and could not make up the revenue, it was potentially ruinous, because the payment to the government was paid upfront, and not based on actual revenue collected. It was a gamble. Secondly, the “debt pyramid” that Eu Chin controlled was considerable. Successful smuggling and the sale of smuggled goods required the complicity of those who were involved in its distribution – the small-time traders, plantation owners, and labour brokers. Their indebtedness to Eu Chin, their financier, made it possible for them to be co-opted into Seng Poh’s schemes.

Seng Poh managed to control the Singapore opium farm by 1863. 98 Trocki, Opium and Empire, 119 gives a timeline based on various sources His next target was the opium farm of Johore. This was then under the control of Tan Hiok Nee, the Major China of Johore (leader of the Chinese community, answerable to the Johore government), who had the ear of the new Temenggong, Abu Bakar. In 1864, Abu Bakar promulgated the Tanjong Putri Regulations, which required all boats coming to and from Johore to stop at the port of Tanjong Putri before they could carry on. 99 Turnbull, “Johore Gambier and Pepper,” and Trocki, Prince of Pirates. Previously, the boat traffic proceeded directly between Singapore and the kangs along the various Johore rivers. This new regulation was an attempt to draw a boundary between Johore’s and Singapore’s economy, and also gave more power to Tan Hiok Nee, because this made it much easier to control the opium traffic to Johore. By channeling everything through the designated point of Tanjong Putri, Johore could limit the influence of investors and financiers in Singapore town.

Naturally, Seah Eu Chin’s interests were badly affected by the new regulations. It is probably no coincidence that the Kongkek was formed around this period. The Kongkek, representing the combined interests of the major pepper and gambier traders, could have exerted pressure on Johore by putting a hold on its investments in that state. The Johore state earned most of its revenue from pepper and gambier agriculture; without investment and more importantly without the cooperation of merchants in Singapore, who set the price for the purchase of gambier from farmers, its solvency would be threatened. It is likely that such pressure, though not given as the official reason, caused the Temenggong to rescind the Tanjong Putri regulations in 1866. Around the same time, Tan Seng Poh found his way into the opium and spirit farms of Johore, and by the end of the year he controlled both the Singapore and Johore farms. 100 Trocki, Opium and Empire, 140-141.

Seng Poh did have a power base apart from the Seah family’s hold over pepper and gambier cultivation. After the triumph with the Johore farms, he had to deal with Cheang Hong Guan, Hong Lim’s brother, who was a serious threat to Seng Poh’s position. Seng Poh supposedly controlled (based on the testimony of Tan Kim Ching in 1883) a faction known as the Seh Tan 氏陈, the “Tan clan”, men of the Tan surname whom he could draw upon for smuggling operations and as fighting men. 101 quoted in Trocki, Opium and Empire, 146. The Teochew Seh Tan was implicated in clashes with the Hokkien Ghee Hock, possibly representing Tan Seng Poh vs. Cheang Hong Lim respectively. This was the strategic advantage that Seah Eu Chin earlier had lacked in his attempts to edge out the Ngee Heng Kongsi – a group of fighting men, a “military” means to forcibly extend his control.

Maurice Freedman posed the question about Chinese in Singapore, “how far did ties of kinship and marriage enter into commercial operations?” 102 M. Freedman, “Chinese Kinship and Marriage in Singapore,” Journal of South-East Asian History 3, no. 2 (1962): 73. In Seah Eu Chin’s case, the answer is “very much”: Seng Poh’s success was built upon the foundation laid by Eu Chin. The success of Eu Chin’s sons, especially Liang Seah, was in turn built upon the success of their uncle and their share in the revenue farms over which Seng Poh had managed to gain control. Although it took quite some time to reach fruition, Eu Chin’s choice of in-laws was a very astute one. Tan Ah Hun, his father-in-law, also did well for himself by having his young son accompany his daughter when she went to Singapore to marry Eu Chin. Tan Seng Poh was trained in an environment that predisposed him to success. Such arrangements served to keep wealth in the family, concentrating it both to benefit family members in the moment, and also as a source of capital for future investment. This is a strategy found in many societies but particularly well-known in communities of Chinese overseas.

The era of pepper and gambier agriculture was still fairly robust after Eu Chin’s death in 1883, but it was soon to be eclipsed at the turn of the century by rubber and tin. From the description of the Chinese official Li Zhongjue 李钟珏, visiting Singapore in 1887, it seemed like business as usual: Singapore was still the centre for the trade, no longer producing much of its own but acting as the distribution centre for pepper and gambier producers in the region. Its annual trade still numbered in the tens of millions of dollars. Gambier production was controlled by Chinese merchants, with the approval of the Johore Sultan, and the trade was still dominated by Teochews; other dialect groups found it hard to break into their turf. 103 李钟珏 [Li Zhongjue], 《新加坡风土记》Xinjiapo fengtu ji (1895); reprinted in《新加坡古事记》Xinjiapo gushi ji, comp. and ed. 饶宗颐 (Rao Zongyi) (Hong Kong: 中华大学出版社, 1994), 165. Soon after the turn of the century, gambier exports and prices started falling, never to recover. 104 Trocki, Opium and Empire, 186-190. The exports from Malaya were undergoing a turnover, catalysed by the entry of Europeans into Malayan agriculture, using industrial principles for cultivation and processing, and Asian labour (mostly Chinese and Indian immigrants). Where previous European agricultural ventures had failed (such as the planting of nutmeg), these would succeed and displace Chinese-run plantations from the agricultural scene. Of the great Malayan exports of the early 20th century, the Seah family’s investments were represented chiefly by Liang Seah’s fame as the “Pineapple King”, growing and selling canned pineapples, and some smaller investments in rubber. 105 Song, One Hundred Years’ History, goes into more detail on his accomplishments. But in terms of relative scale, these could not compare to the achievements of his father (and uncle) in dominating the economy of the region.

What Tan Seng Poh had accomplished was undone fairly quickly. A new player, the Penang syndicate, had moved into the scene, and from the 1890s onwards had a controlling hand in the Singapore farms, even though some of the Seah sons and grandsons (Song Seah and Pek Seah, the third and fourth sons of Eu Chin, and Eng Keat, oldest son of Cheo Seah, Eu Chin’s oldest son) were farmers in the Singapore and Penang syndicate between 1898 and 1900. 106 Trocki, Opium and Empire, 192. Opium farming, and the revenue farm system in general, would continue to the 1910s but thereafter be abolished. By that time, opium accounted for almost half the government's revenue. Instead, the government took over opium production directly, setting up a factory at what is today known as Bukit Chandu (“Opium Hill”) in Pasir Panjang.

Photograph of the Old Government Chandu Factory (external link)

Previous (Reaching the Top) | Back to Life | Next (Property & Risks)