Influence and Leadership

声势与领导

Cultivating Leadership Position within the Chinese Community

华侨社会中的领导状态

Chongwenge

崇文阁

The Chinese are reputed for their regard for education, so it is no surprise that among Eu Chin’s charitable activities within the Chinese community was donating to the cost of one of the first Chinese schools in Singapore, the Chóngwéngé 崇文阁 School. 33 There were, according to Song (One Hundred Years’ History, 29) who quotes a German missionary, already two private schools in Singapore, one Cantonese and one Hokkien, by 1829, though there may have been other forms of private tuition before this. Schools like Chongwenge and Cuiying, however, represented community efforts to promote education rather than private schooling for those of means, and so can be considered separately. According to the commemorative inscription in the Thian Hock Kheng 天福宫 temple, it was built from 1849 to 1852 (predating the Cuiying school 萃英书院, which was founded in 1854) as a pavilion within the temple grounds. 34 “Xingjian Chongwenge Beiji” (兴建崇文阁碑记, dated 1867) in 陈荆和,陈育崧 [Chen Jinghe, Chen Yusong], 《新加坡华文碑铭记录》Xinjiapo huawen beiming jilu (Hong Kong:中华大学出版社, 1972), 283-4. The inscription also records donors to the building of the school, and the amount they donated, and Seah Eu Chin was among the main donors, donating a sum of $200. Even more interesting than the amount he gave is the regional-origin and dialect composition of the donors, for Thian Hock Kheng was the main Hokkien temple, and Chongwenge was associated with it and was thus a primarily Hokkien institution. Therefore almost all the other donors, excepting a Hakka, Lau Joon Teck 刘润德 , were Hokkiens, and their names also appear in inscriptions for other Hokkien institutions built around the same time, like the Heng Shan Ting. 35 See 柯木林 [Ke Mulin], “崇文阁与萃英书院” in《石叻古迹》Shile guji, 林孝胜 [Lin Xiaosheng] et al. (Singapore: South Seas Society, 1975).

Why would a Teochew be willing to donate to a Hokkien institution? A few possible reasons have been suggested. First, his gambier and pepper business and other business interests necessitated frequent business contacts with Chinese of other dialect groups, especially Hokkiens, who made up a sizeable proportion of the mercantile class. Since his wealth and influence were sizeable not just for a Teochew but for the whole Chinese community in Singapore, it would make sense for him to support charitable endeavours started by other bangs that would benefit the Chinese community as a whole. Second, there are few subjects as symbolically dear and important to the Chinese as education, so supporting education, regardless of bang affiliation, would not just have been politically savvy but also something expected of him as a community leader. Third was his reputation as a scholar of the Chinese language: while the Chinese traditionally (in theory, at least) revered the scholar-official 士 class, the immigrant society in Singapore had a lopsided social stratum where the merchants 商 had the most wealth and power, so in their minds, Eu Chin probably commanded the best of both worlds as a merchant with scholarly leanings, thus they would naturally have sought his support for the school.

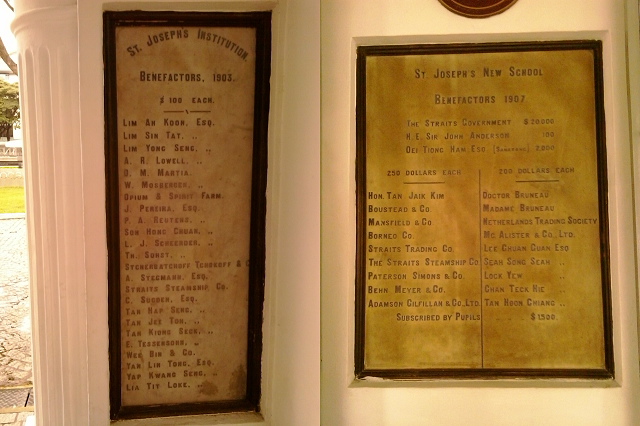

By the next generation, however, the political circumstances of the Seah family had changed, and when the Teochew community set up its own Tuan Mong School 端蒙书院 in 1906, Seah Liang Seah was absent from the initial management committee despite still being director of the Ngee Ann Kongsi, indicating the Seah family’s gradual displacement from the leadership of the Teochew community (and its eventual closer association with the colonial establishment than with the Chinese community leadership) that culminated in the foundation of the Teochew Poit Ip Huay Kuan and the takeover of the Ngee Ann Kongsi by the faction led by Lim Nee Soon. A member of the Lim faction, Yeo Chan Boon, was in both the founding board of the Tuan Mong School and the board of the new Ngee Ann Kongsi. The Seah family’s shift in emphasis towards cultivating relations with the colonial establishment can be seen in Seah Liang Seah’s donation of $1000 in silver dollars to the King Edward VII Medical College 36 See〈七州府医学堂碑记〉transcribed in 庄饮永 [David K.Y. Chng],《新甲华人史新考》Xinjia huaren shi xinkao (Singapore: South Seas Society, 1990), 176-8. and Seah Song Seah’s donation of $200 to Saint Joseph’s Institution. 37 See inscription on the former St. Joseph’s Institution building at Victoria Street, now the Singapore Art Museum. Other years’ inscriptions record donations by Seah Eng Kiat and the Opium and Spirit Farm, which the Seah sons had stakes in as well. As for Chongwenge, it later became the Chong Hock Girl’s School, today’s Chongfu Primary School 崇福学校 run by the Hokkien Huay Kuan.

Previous | Back to Influence | Next (Colonial government)